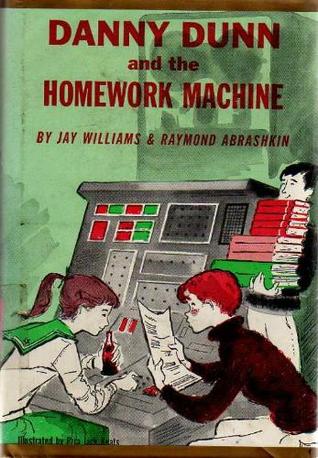

This week’s Friday Fiction is inspired by Rachel Manija Brown, who reminded me about the “Danny Dunn” series by Jay Williams and Raymond Abrashkin. They were quite formative for me, so thank you Rachel!

The first book came out in 1954 and the last in 1977. The first handful featured Danny Dunn (a curious kid way too smart for his own good), his friend Joe Pearson (a hilariously mopey budding poet and writer), and Professor Bullfinch (basically your stereotypical jolly scientist, for whom Danny’s mom is a housekeeper). Later on, Irene Miller (a Cool Girl who is just as into/good at science as Danny, her father is also a scientist) joins the team. Sometimes Professor Bullfinch’s frenemy Dr. Grimes shows up.

The books are written for older kids in school–you generally need some scientific understanding to enjoy them. They’re pretty fun, and very funny, and frequently formulaic. The formula runs something like this: Professor Bullfinch is working on something scientific. Danny et al mess with it in some manner. Adventure and shenanigans ensue!

Danny Dunn plots were usually a blend of adventure and SF, although some of the them were adventure-only. Like the one where they got stranded on a desert island. Anyway, the SF ones were probably the first SF books I ever encountered. I honestly can’t remember how old I was when I discovered the series. A kid for sure. A kid who hadn’t yet heard the bigram “science fiction.” But even if I had, I’m not sure I would have applied the term to the books.

Here’s an example. One of the first books I read was “Danny Dunn and the Homework Machine.” The main plot concerns Professor Bullfinch’s enormous computer (think UNIVAC and punch cards). When the professor leaves on a business trip, Danny promptly uses it to do his homework (proving the authors truly understood kids). I’m not a youngster, but when I was in high school, we had a standing PC at home. Danny Dunn’s machine was another world away. It was science fiction, all right … historical science fiction.

However, it was quite accurate, which I didn’t realize how much I appreciated until I got older and attempted to learn Java and Python. In that story, Professor Bullfinch had previously taught Danny how to program the computer. Danny realizes that he can use programming to do his and Joe’s homework, especially computation-heavy subjects like math … and does so. After he turns in the typed pages, his teacher objects on the grounds that it is not really “doing the work” if a computer is doing it for you.

Danny retorts that you have to understand the problem in order to program it well enough to have it do your homework, so he is totally “doing the work,” he is just being efficient (and perhaps a bit smug) about it.

Danny’s mother (more similar to Danny than he figures) realizes that while this is true, it is also Danny’s strategic weakness. So she gives a suggestion to Danny’s teacher that she call Danny’s bluff. And she does! She tells Danny that since he is SO advanced, and SO smart, then she should assign him more advanced work. After all, he’s got a computer to do it for him. Danny charges ahead but quickly realizes that it is a lot of work to do learn new knowledge and then to program it sufficiently that he can get the computer to spit out answers on command! Mom and Teach were right all along.

Curiously, debugging is not part of the plot. Just as well, I think poor Danny had enough to deal with at that point. Eventually he admits defeat and goes back to doing homework the old-fashioned way. The book ends on a brief discussion of humans vs computers and the professor declares that no matter how smart they get, computers will never have human creativity. (Someone needs to write the fanfic where Professor Bullfinch encounters story-writing neural networks.)

As you can extrapolate, the books were wholesome and fun and it was so nice to see a girl interested in science who was never, ever condescended to in the text. (Okay–Danny briefly tries, is slapped down hard, and never tries again.) In fact, Irene had some leading roles in the science plots. She made it seem incredibly natural and fitting that girls should be interested in science and should pursue a scientific career.

I have told some incredulous people that I never felt–as a child–that as a girl, I was unfit for science. Although I eventually encountered sexism and misogyny in science, that did not happen until college and graduate school–so judging by some stories I’ve heard, I was very lucky for a time. Which is a somewhat sad assessment, but that’s a different discussion. The point is that the Danny Dunn series were an extremely important part of my childhood experience that eventually led me to trying my hand at a science career. (It didn’t work out, but that’s hardly the books’ fault.)

Speaking of science careers, where would Danny have ended up? From the books, Danny is clearly ahead of the curve on intelligence. It’s unclear just how much, but I could easily see him going to–for instance–MIT for college. At the very least, he’d have one hell of a personal statement. Perhaps he would have pursued graduate school afterwards, although I could just as easily see him setting up a tinkering lab and inventing something and starting his own company.

And having known a lot of people with that level of intelligence, I must say that what really and truly stands out about the Danny Dunn series to me–at a level that approaches fantasy–is how ridiculously and wonderfully well-adjusted he is. If he continues down his path in life, he’s going to be the polar opposite of the Tortured And/Or Asshole Genius archetype. He has a best friend who is not into science but who is his equal! He is kind to an equally smart and well-adjusted girl! He still has a lot of room to grow (see above). When he messes up, he fesses up. His intelligence is occasionally no match for judiciously applied wisdom and experience (see above). And he still needs and loves his friends and his family.

As a former Smart Child, I used to wish I was smarter. But–to mangle that quote from Harvey–today I think it would be nicer to be more loving, and to be more loved. But of course, I hope Danny Dunn and his family and friends went on having both in their lives.